Naval Observatory gives rare look through the lens of its ‘prolific’ 150-year-old telescope

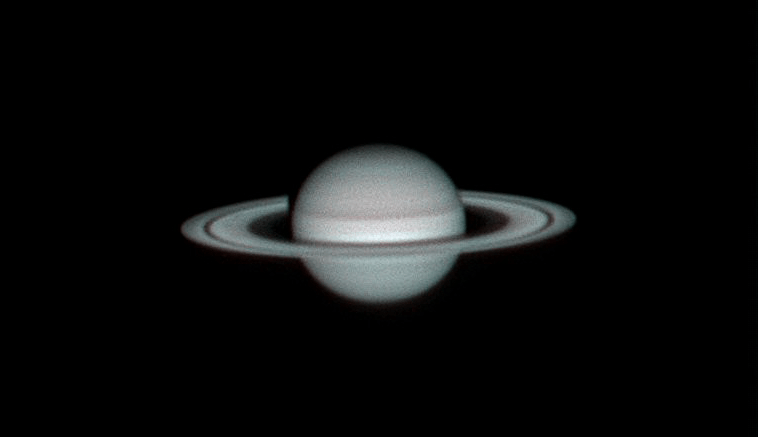

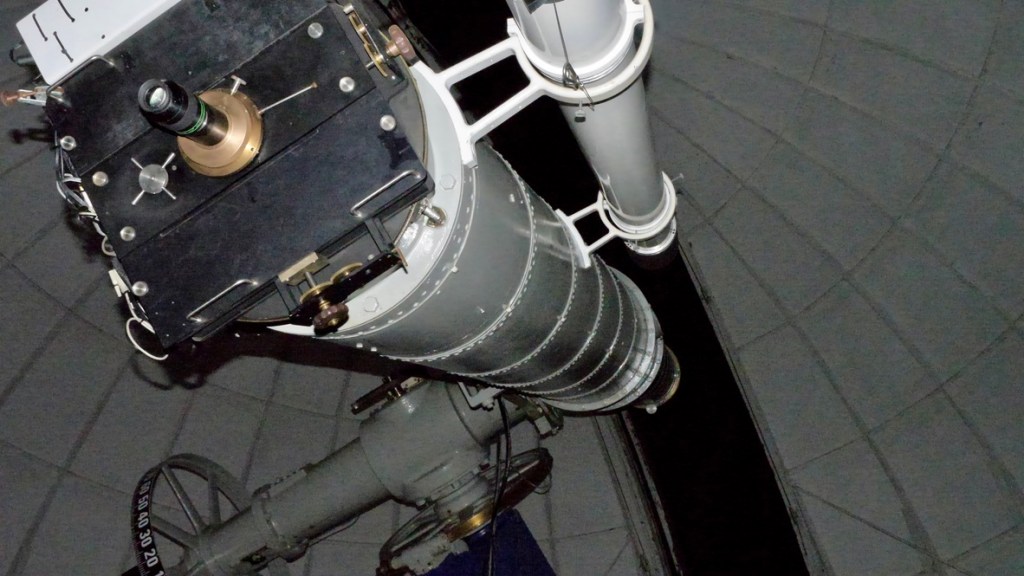

On two clear nights in early November, current and former government astronomers and other guests (including DefenseScoop) each got multiple chances to peer through the eyepiece of the United States’ 26-inch aperture “Great Equatorial” telescope at the Naval Observatory in Washington to observe Saturn and distant galaxies and stars with their own eyes.

It’s not often that the observatory opens its doors to let groups from the public come in and engage with its powerful tools — but this rare opportunity was part of its celebration of that telescope’s 150th anniversary.

The device has enabled a number of scientifically significant observations in its lifetime since a select group of Naval Observatory astronomers got to gaze through it for the first time on Nov. 12, 1873. Enhanced by technology modernization efforts in recent years, today it continues to supply the Navy and other Defense Department components with crucial astronomical data.

“There’s a ton of history here. We are really proud of the work, not only of the telescope, but of the people who have maintained it over the years. All this work to do the automation, to install the encoders to the motors and all that — that was done here, in-house,” Geoff Chester, a public affairs officer and astronomer who has been with the observatory for almost 30 years, told DefenseScoop in a recent interview.

The telescope has a unique American backstory that stems to 1867. Among its many impacts, it was used by Naval astronomer Asaph Hall to identify the two moons of Mars, which is considered among the most important 19th century astronomical discoveries.

“The primary mission of the telescope — for pretty much from the get-go and up, through most of the 20th century — we’ve been focusing primarily on two classes of objects,” Chester explained.

The first are the moons of planets, and especially those of the outer solar system.

“When it came time to plan out the Voyager missions that flew through the Jupiter and Saturn systems back in the mid-to-late 1970s, they needed very precise measurements and tables to predict where the moons of those planets were going to be so they can target fly-bys of all this. Just the celestial mechanics aspect of it just boggles my mind sometimes. But we had an astronomer here who spent probably the better part of 10 years photographing the positions of those moons on every clear night when they could be seen,” Chester said.

The telescope’s other primary use involves measuring the astrometric properties of double stars.

Broadly, “double” or “binary” stars essentially appear with the naked eye to be in very nearly the same line of sight but actually belong to separate star systems that can be incredibly far apart.

“Binary stars actually make up the majority of stars that you see in the sky, and the majority of those are actually physical pairs where you’ve got two stars that are orbiting their center of mass. One of the missions that we have here is to determine the precise positions of objects — not only right now, but where they are going to be 15, 20, 30, or 50 years from now — because we have some systems that are like geostationary satellites and that sort of thing, which can’t use GPS to locate themselves in space,” Chester said.

If the observatory’s experts can’t make accurate measurements of double stars, they are not able to predict what their orbits would be around each other — and how that would affect the apparent positions of the components of those stars.

This telescope has been fueling double-star observations from the Naval Observatory’s site since 1893, and it hasn’t changed much optically and mechanically since.

“It’s a very, very long-standing database. Now, recently, we have automated the telescope so that it will actually go through a computerized observing program [with] a list of objects for each night. And it has a new detector on the back that allows us to measure the properties of the double star in about two minutes instead of the old, hour-plus that it used to take to do it visually. So we have huge, tremendous throughput now,” Chester explained.

At this point, the telescope has made about 55,000 individual double-star measurements.

“It’s the most prolific double-star telescope in the world. And it is also the oldest continuously operating research grade telescope in the world,” he noted.

Accurately measuring objects like double stars requires precise optical parameters. Large refracting telescopes like the Great Equatorial are particularly suited for such observations — but since the end of the 19th century, virtually all the big telescopes that have been built for professional observatories have been reflecting telescopes.

“And optically, they are just not as good for observing double stars as these big old refractors are. So, that’s why we keep it going. And with any luck, it’ll keep going for another 50 years,” Chester told DefenseScoop.

Tune into the complete interview with Chester on the DefenseScoop Podcast.