Data passed ‘at a magnitude never seen before’ at Army’s Project Convergence

CAMP PENDLETON, Calif. — The Army, joint services and select multinational partners successfully passed battlefield data to an extent never before seen in a capstone experiment taking place in February and March, according to senior defense officials.

Project Convergence Capstone 4, as it is called, is taking place in two phases: Phase 1 occurred at Camp Pendleton from Feb. 23-March 3 and was joint-focused, integrating offensive and defensive fires as well as defeating a large target array. Phase 2 will occur at Fort Irwin March 11-20 and will be more Army-focused. Project Convergence is hosted by the Army and provides an experimentation venue for the joint services and multinational partners to test capabilities and concepts associated with the Pentagon’s top priority called Combined Joint All-Domain and Control (CJADC2).

CJADC2 envisions how systems across the entire battlespace from all services and key international partners could be more effectively and holistically networked and connected to provide the right data to commanders for better and faster decision-making.

“The entire joint force, and with our U.K. and Australian teammates and allies, we were able to effectively move data for the first time in an Indo-Pacific scenario at a magnitude never seen before,” Lt. Gen. Ross Coffman, deputy commander of Army Futures Command, told reporters during a visit to Project Convergence March 5. Coffman noted it was ten times what the experiment resulted in a year ago.

Officials noted that this isn’t an end state. Project Convergence is a continuous experimentation effort that ties into several exercises across the Pacific and European theater, gaming concepts and technologies for greater connectivity to enable faster decision-making.

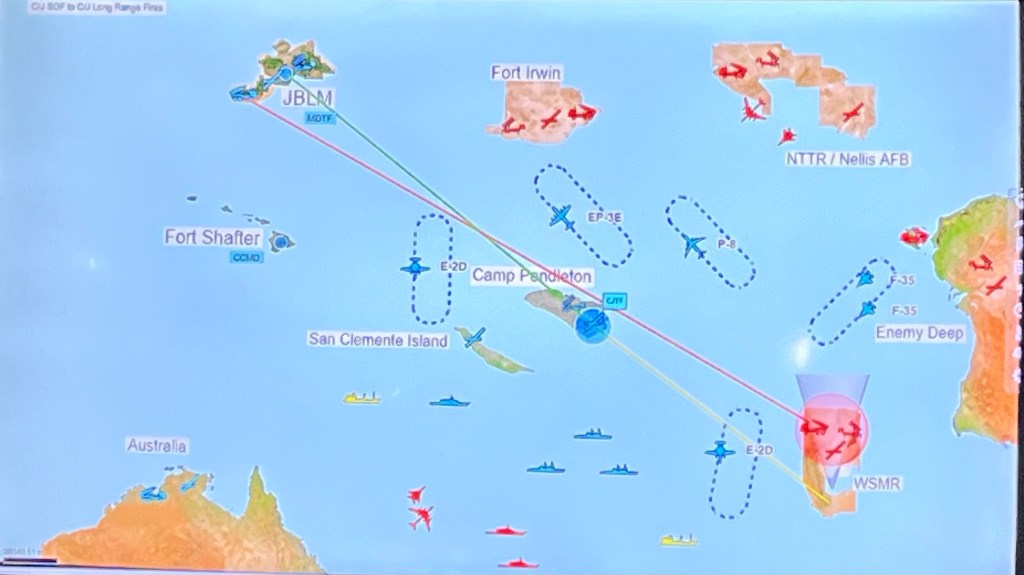

The experiment simulated the vast distance of the Pacific by having participation from Australia all the way back to the continental U.S. as far as New Jersey, with water simulated in the continental U.S. There were forces, capabilities and threat forces playing from Australia, Hawaii, Joint Base Lewis McChord, Camp Pendleton, Nevada test range and Nellis Air Force Base, Fort Irwin and White Sands Missile Range.

Phase 2 will involve a complete battle handoff of data from XVIII Airborne Corps at Camp Pendleton to III Corps at Fort Irwin. This means the Army will test sharing and sending data from one corps to another to continue operations.

Officials were sparse on specific details regarding what types of data were passed, aside from general targeting information, or how that data was passed. However, many officials noted the key to Capstone 4 was being able to pass data quickly.

“The aim point really for all of capstone experimentation is to be able to pass information from the edge to the decider, whoever that decider is, wherever that C2 node is located … and then to the effector at machine speed, reducing transcription times, or, for instance, type in or copy and paste or answer the phone to pass that message,” said Maj. John Donaho, capability integrator team leader at Joint Modernization Command.

He went on to explain that the legacy way of doing things involved phone or radio calls that would bounce around from various units to headquarters and back delaying the time to affect a target.

The goal is to get to what Donaho called “joint integrated sensor netting,” essentially where sensors can talk to each other, allowing humans to understand the information and pass it seamlessly to the right unit or capability best positioned to take action. For example, that could be ships sharing information with an aircraft that then shares that information with land-based capabilities.

“Every service developed programs that support service requirements and that’s how it works. The Navy is going to solve Navy problems, the Army is going to solve Army problems,” he said. “However, 21st-century conflict is a team sport. It’s not just a Navy problem, it’s not just an Army problem, it’s not just a U.S. military problem. It’s a combined and joint problem working through not just our joint partners, but also our allies and mission partners to accomplish a shared and state.”

In one portion of the scenario, special operations forces, who inserted themselves within the enemy battlespace as is their key role in helping shape operations for the joint force, were able to pass data back to the combined joint task force to issue tactical fire direction.

In a fires example, Col. Matthew Rauscher, director of Fires Capabilities Development and Integration Directorate at Fort Sill, explained that the passage of data was the objective of the experiment, not the time it took from identifying a target to firing.

“For us, the experiment really was from the point of sense to passing the data to the effector. That was what we were really focused on [with] this,” he said.

Elsewhere, officials described how BEAST+ — a small backpack-based system for direction-finding targeting, with an electronic attack capability added on, if needed – successfully relayed electronic signals from soldiers on the ground at White Sands Missile Range to the command center at Camp Pendleton for them to take action against. This was a big milestone for those teams to be able to find signals of interest and transmit them to higher headquarters to better understand the electromagnetic spectrum environment and, if needed, allow more advanced time for reprogrammers to make adjustments to those signals of interest.

Officials described a series of cross-domain solutions and bridging capabilities that enabled data to pass from the sensors of one service to another, or even to an international partner.

However, in many cases, those cross-domain solutions had to be tweaked throughout the experiment.

“Our cross-domain solutions, in some cases, were not optimal and had to be reprogrammed to work. At the end, we were able to work through these glitches and ensure that we can pass data across the coalition and across the joint force. But when you put stress on untested equipment, you’re going to learn things,” Coffman said. “What we learned very quickly is that when you’re passing that volume of data, there’s other legacy systems that weren’t designed initially for that amount. We have to open those up, and we’re able to do that. But you just don’t know what parts and what software needs to be modified to take that volume of data. Initially, that gave us some trouble and then we were able to work through it.”

Coffman described a bridging capability that enabled the passage of defensive information data to everyone on the network.

“This bridge absolutely allowed us to pass information from multiple sensors to multiple shooters so that an Army sensor passed data to a shooter in every service and every service sensor passed the same to every other service,” he explained. “It was able to pass an amount of data that we have not seen before. We tested it last year, it was nascent, and we were able to pass data successfully. But now by increasing 10-fold, it absolutely was able to pass that data and get it to the right shooters.”

When it came to the network itself, officials said it responded well and was impressive.

What “used to take us days and hours is just taking us minutes now, to put those things and make them work together, which has been really, really impressive to watch,” said Maj. Gen. Jeth Rey, director of the Network Cross Functional Team, adding that this is the third Project Convergence he’s participated in.

Col. Heather Fisk, who served as the Capstone 4 G6, explained that participants saw increased ability to get information from a sensor to a decider to a shooter at faster speeds.

“We’ve been experimenting with some technologies that enable us to do that at machine speed and it has increased our ability to do Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control and situational awareness synchronization with our multinational partners,” Fisk said. “We’ve seen these technologies improve how we can share our common operational picture, synchronize with our joint and multinational partners and also share not just our common operational picture, but our common intelligence picture as well.”

Essence of CJADC2

Officials explained that developing a joint and multinational common operational picture – one that allows everyone to have the same picture of the battlefield with the same data – will make executing operations more efficient, especially from a munitions perspective.

“Without experiments like this, when a threat arises, the Marine Corps would shoot at it, the Navy would shoot at it and now we have three missiles … the Air Force is firing, now we have four. With this, with that common operational picture, we’ve identified the ones so we don’t waste missiles needlessly and we’re all shooting at the same target,” Coffman said.

Others described the end state as a single magazine.

“What Convergence allows is … us to operate with one single magazine across the joint force. If we can’t connect ourselves together, then we’re going to build individual stovepipe plans and we may end up double-targeting or triple-targeting as we each build a plan that sits on top or next to one another,” said Vice Adm. Michael Boyle, commander of Third Fleet. “But if we can connect together, then we can draw from a single magazine across the joint force … We don’t have unlimited magazines.”

Boyle noted that while it’s not the operational force’s or the exercise’s role to fill the magazines, it is their job to “ensure that we can connect my sensors to his fires and his sensors to my fires because I might have the most available weapon where he’s got the most survivable sensor and vice versa.”

“That’s really what this is about: It’s enabling us to pick from whatever magazine we would need to pick from,” he added.

Getting from experiment to real-world operations

Project Convergence aims to experiment with new technologies and concepts, which ultimately inform potential requirements for systems to be deployed. Officials described how the experiment sought to help inform those approaches and even make their way into real-world operations and units after successful demonstration.

“I view Convergence as the opportunity to test that the lightning bolts are possible. Lightning bolts on slides where we see collectors connected to effectors or the collection assets connected to the fires elements that are going to deliver effects to our adversaries,” Boyle said.

He noted that as the Third Fleet commander, with responsibility for naval forces in the Pacific, he brought real, actual platforms and capabilities to Project Convergence, namely the USS Paul Hamilton, USS Momsen, USS Savannah, E-2D Advanced Hawkeyes and EP-3s.

This was done, Boyle said, to “put some real live program of record assets and demonstrate that we can connect that capability to the experimentation that’s happening across the joint force and connect it to other program of record capability. That gives me the confidence as an operational commander, that if asked to synchronize these joint effects I could.”

The experiment also allowed teams to practice mission rehearsal with planners present.

“The planners that were also here executing this experiment can say, ‘I know this can be done. I saw it done during Convergence. Let’s figure out what part of that machine has to be turned into a program of record so that I can put it on my watch floor and execute during those mission rehearsals,’ which then gives me that fight-tonight capability using the joint force,” Boyle said. “What I’m really describing is requirements generation, so then, as an operator, I now know that it’s possible. I know it’s not theoretical, it’s possible. Then I can very clearly define I need to have the capability that was demonstrated during Convergence.”

The lessons from Project Convergence will be brought forward to the next Pacific exercise and Europe exercise so they are continuously improved, Coffman said.