Report: Space Force must accelerate work to field capabilities for dynamic space ops

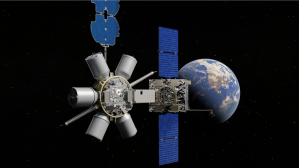

As the space domain becomes increasingly complex, the Space Force must look beyond on-orbit refueling capabilities in its quest to enable dynamic space operations, according to a new report.

The research paper, which is set to be published by the Mitchell Institute on Thursday, focuses on the much-deliberated topic of how U.S. Space Command should conduct mobility and logistics on orbit, as well as how the Space Force could develop and field capabilities to do so. Broadly, the report calls on the service to consider ways to increase its flexibility and maneuverability across the entire space architecture — not just its assets on orbit.

For years, leaders at Spacecom have publicly stated that the combatant command needs capabilities to conduct what it calls dynamic space operations (DSO), or the ability to continuously and quickly maneuver in space over long periods of time and distance.

Initial research-and-development funding and demonstrations have been directed towards refueling satellites in space, but the concept can be realized through a number of other capabilities, according to Charles Galbreath, senior resident fellow for space studies at the Mitchell Institute and author of the new report, titled “A Broader Look at Dynamic Space Operations: Creating Mutli-dimensional Dilemmas for Adversaries.”

“I’m defining dynamic space operations … not as maneuver without regret or sustained space maneuver, but anything that increases the versatility, adaptability and maneuverability of our space architecture — both in a physical space as well as in the electromagnetic spectrum,” Galbreath told reporters Tuesday ahead of the report’s publication.

To that end, the Space. Force can pursue options for dynamic ops not only for its space-based platforms, but also its ground operations, link segments and launch facilities. Galbreath emphasized that, given advancements in space technologies by U.S. adversaries, the Pentagon should consider how these alternatives can enable DSO and accelerate them.

“Hesitancy to fully implement dynamic space operations at scale risks ceding valuable time and initiative to adversaries. The Space Force must move decisively to embrace all opportunities of this new operational paradigm,” Galbreath wrote in the report.

The service is already moving ahead on a number of programs and capabilities across its architecture that can enable these types of ops — particularly for space-based assets. The technology for on-orbit refueling has become especially mature, as indicated by the Space Force’s decision to make it a requirement for its new space domain awareness constellation known as RG-XX, Galbreath said.

Refueling a military satellite would give it the ability to move on orbit without the risk of running out of fuel, meaning operators could perform more unpredictable maneuvers to surprise or evade adversaries. Another option would be exploring novel propulsion capabilities — including nuclear or plasma engines — although Galbreath noted more research is needed to fully understand the possibilities.

“What we have to do is recognize where we are with that technology and where we are in terms of the operational requirement that that might satisfy,” he said. “We leverage electric propulsion today. It’s a highly efficient form of propulsion, but it does not have the thrust-to-weight ratio you might need to maneuver out of the way of a threat, or maneuver to such an extreme that adversaries lose track of where we are.”

But there is more the Space Force can do to make its space assets more dynamic beyond maneuverability and propulsion systems. Building more modularity into platforms could allow for subsystems to be upgraded on orbit or completely swapped out, which could extend a satellite’s lifespan or broaden its missions, Galbreath said.

Mission flexibility can also be achieved by integrating reprogrammable software.

“If we have a modular capability that has potential to generate more power [or] change waveforms, you might have a satellite that’s sending out communication signals one day, position, navigation and timing signals another, and on a third day, potentially even jamming capabilities. That would keep the adversaries guessing about what the capabilities and limitations of your assets are,” Galbreath noted.

The Space Force should also explore ways to make its terrestrial sites and data links more flexible, Galbreath said. In the report, he noted that the service operates only a few fixed ground stations to operate satellites, while the frequencies used to control and interact with systems in space are well established — meaning both are vulnerable to attack from adversaries.

The Space Force has taken recent strides to modernize its ground systems, such as through the Rapid Resilient Command and Control (R2C2) program — a cloud-based system able to maneuver satellites from anywhere in the world to complicate adversary targeting.

R2C2 will also employ phased array antennas that can contact multiple space vehicles at once under the Satellite Communications Augmentation Resource (SCAR) program.

“If we can employ these techniques to a broader set of satellite programs, we might be able to move away from just basically well-secured facilities in central Colorado and be able to operate in a more dynamic and mobile approach in the future that adds a layer of resilience,” Galbreath said. “The phase array antennas related to SCAR move us away from the [radio frequencies] where you have a point A to point B, and we can actually have contact with multiple satellites simultaneously.”

As for data links, Galbreath noted that concepts such as frequency hopping and path-agnostic connectivity would make it harder for adversaries to know the exact segment being used to transmit data to and from space.

Laser crosslink technology being developed for the Space Development Agency’s Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA) will be crucial moving forward, as it uses optical signals with smaller footprints that are more difficult to intercept, he said.

Finally, Galbreath argued that implementing dynamic space operations can be extended to the Space Force’s launch capabilities — primarily through diversification of launch sites and launch vehicles, as well as developing more flexible launch manifest procedures.

“Cumulatively, this enables the exchange of one payload for another aboard a booster on demand, which could create a more dynamic launch manifest that will respond better to urgent warfighter needs,” he wrote in the report.

In the end, achieving dynamic space operations will require prioritizing investments in the capabilities, as well as development of associating concepts of operations and supporting architectures, the report noted.

And while the concept of dynamic space ops is still relatively early on in development, current budget constraints and competing priorities could further delay implementation, Galbreath said. He called on the Space Force to continue funding for DSO research and development efforts, and on lawmakers to provide more funding to speed up procurement.

“I believe that the Space Force has heard the demand signal, and I think they recognize the value that is intrinsic in pursuing dynamic space operations,” he said. “I think that they are also realizing the fiscal reality of where their current budget is — ‘these are great things to do if I had the resources to do it, but right now I’m not even equipped and resourced to do the missions I have.’”