Getting better tech faster: The benefits of new technology legislation

America’s Navy faces a challenge: maintaining readiness with a strained industrial base in the face of rising threats. Ships are harder to maintain, repairs take too long, and outdated processes prevent proven technologies from reaching the fleet.

Fortunately, leaders have moved thoughtfully to fix these problems through recent reconciliation funding and the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2026. This provides the Navy with exactly what it needs: clear, expedited pathways to qualify and adopt high-value technologies that strengthen readiness and support Sailors on the deck plates.

The benefit isn’t just a faster qualification process for new tech — it’s having a qualification process at all. The Navy’s success depends on getting mature capabilities into the field.

Laser ablation technology that stalled

Years ago, as a Command Master Chief at Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), I was briefed on laser ablation technology for quickly removing rust from ships. I was impressed and supported introducing it across the fleet.

Laser ablation was first pioneered in 1973 for cleaning cultural artifacts and later, in 1995, for removing aircraft coatings. In 2012, researchers proved it could remove rust from ship surfaces. It wasn’t risky, had been around for decades, had been proven on ships, and yet still hadn’t been introduced to the fleet. Why?

Some critics said we shouldn’t trust 18-year-olds with $100,000 laser ablation machines — even though we regularly trust them with $67 million aircraft.

Others argued that, by removing microscopic metal particles, laser ablation reduced ship service life. True, but that reduction was only a few days — a minuscule difference for ships that last 50 years.

The alternative to laser ablation is a Sailor with a needle gun manually chipping rust for eight hours a day, five days a week. Laser ablation does the job in one-tenth of the time. Even setting aside efficiency, this technology improves quality of life for Sailors doing this work.

Yes, the units cost more: $25,000 (costs have come down) compared to a few hundred dollars for a needle gun. But it becomes a bargain when you consider that time, readiness, and Sailor quality of life are equally compelling metrics — and they are — then laser ablation is the better solution.

An organization designed for ‘No’

Now, as a Maritime Solutions Advisor for Pittsburgh-based Gecko Robotics, I see how the lack of defined qualification processes affects American technology companies.

Within the Navy, the technical community makes qualifying new tech extremely difficult. This is partially by design: the Navy didn’t want folks to accept unreasonably high technical risk when human life was at stake. So, administratively, the Navy made sure Technical Warrant Holders felt no pressure to say “yes” to new technologies. But this setup incentivized an overly cautious approach that stifles experimentation, even when the risks do not outweigh benefits.

So, the default became saying “no.” Or — without clear guidelines for qualification approval — requiring test after test to achieve a qualification approval standard that doesn’t exist. I have been told by a TWH “I’m not sure what I need to approve this, but this is not it. Bring me more.”

No clear path to technology qualification

The impact of this is felt most by technology startups — the very companies that offer so much potential to rebuild our industrial base.

Consider the innovative non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques for inspecting welds using encoded phased array ultrasound technology (PAUT). This decades-old tech still hasn’t been adopted by the Navy. Why? Because NDT requirements in Tech Pub 271, a document first issued in the 1950s, are rarely updated. All the innovation since then? Largely ignored. Because the 1950s version works “well enough.”

But it blocks innovation. When startups show up with new technologies — technologies that can improve quality, save months on schedule, or cut costs — the Navy doesn’t know how to approve them. There’s no clear path to qualification.

With the PAUT solution, we have been through test plates with known defects, blind tests, scrap hulls, and even actual submarine welds. We’ve passed them all. But there’s still no qualification, because there aren’t clear pathways. It is open to interpretation.

So, we go through the tests again. And again. And again.

The manufacturing process is no easier. Shipbuilders have to advocate for adoption, but they’re not incentivized to change. As one shipbuilder told me, “I don’t need to build a perfect ship. I just need to build one that meets the specifications.”

Standards stuck in the 1950s

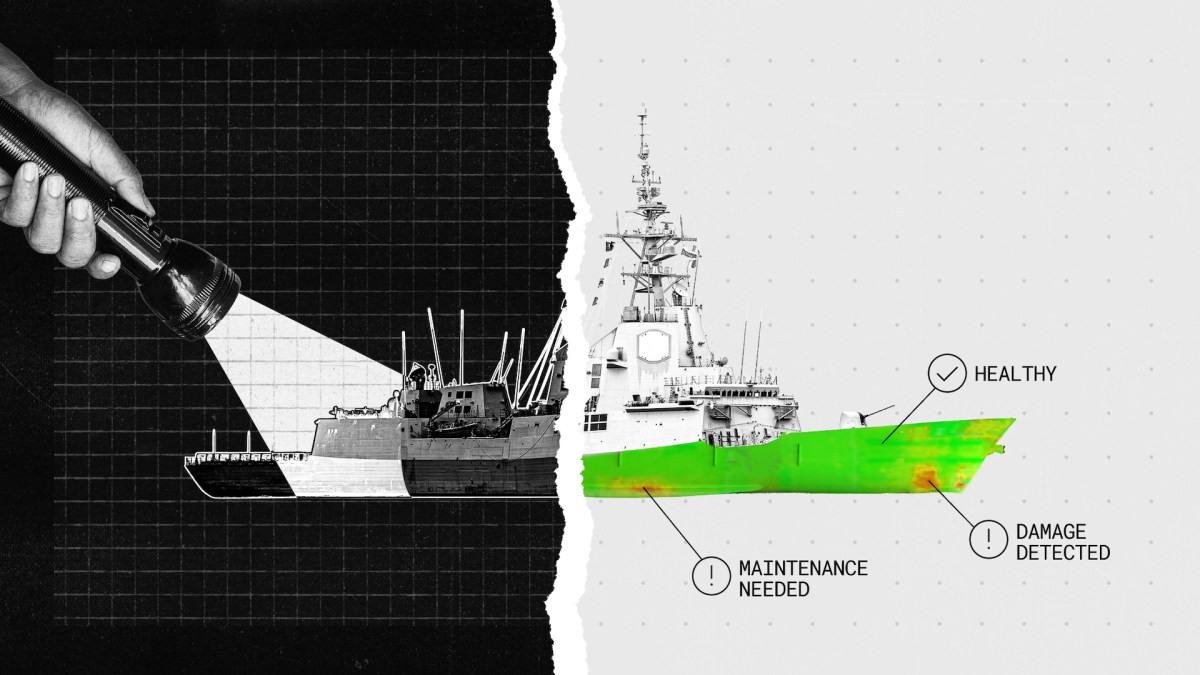

The Navy has been inspecting welds with the equivalent of a flashlight. PAUT is like surgical room lighting. The defects were always there. The old tools just didn’t show them.

We recently scanned a weld on an asset that had been in service for 30 years. Thirty years ago, it passed radiographic and ultrasound inspection. But PAUT showed defects that, under today’s written standards, would have disqualified it for service. The conclusion isn’t that PAUT is wrong or that the weld is bad — it’s that the standards are outdated.

Updating those standards takes time and effort. But we need to do it — now more than ever — because the threat environment has changed.

New tech to counter new threats

After the Cold War, we consolidated shipbuilders, closed shipyards, shifted young people into other careers, and let our skills atrophy.

Fast-forward to now. Near-peer competitors have emerged, something not envisioned in the 1990s, but we now lack the industrial base, the workforce, and the capacity.

Expanding the shipbuilding workforce is crucial. But the real opportunity is in providing technologies that turn workers into superworkers: tools that multiply the amount of work they can do and lower health and safety risks. We must help the Navy adopt them.

Why this legislation matters

That context makes these legislative efforts so important and so welcome. Reconciliation funding directed a billion dollars “for the expansion and acceleration of qualification activities and technical data management to enhance competition in [the] defense industrial base.” Complementing that work, the Senate Armed Services Committee-passed version of the FY26 NDAA would support Navy efforts to investigate, qualify, approve, integrate, and fully adopt advanced technologies on an expedited timeline.

For Sailors, it will mean fewer hours grinding away at rust, and more hours honing their warfighting skills. For shipbuilders, it will mean standards that reflect modern tools. For the new entrants, it will mean greater incentives and a clean pathway to join an industrial base in need of revitalization and new energy. And for the nation, it will mean a Navy that is more ready, more resilient, and more capable of deterring and, if needed, defeating adversaries.

We can’t keep asking Sailors to do 20th-century work in a 21st-century fight. Clear pathways to qualification of new technologies can change that paradigm. I am grateful to see work underway to give the Navy what it needs to meet the challenge.