HII executive wants CVN-80 to be the Navy’s ‘first 3D-printed ship’

HII, one of the leading U.S.-based shipbuilders, is capitalizing on Navy requirement updates and rapidly maturing 3D-printing technologies to save time and money engineering and maintaining some of the military’s most powerful ships.

At a time when supply chain challenges are causing significant delays in manufacturing across the globe, the company is applying additive manufacturing advancements to 3D print some integral parts it needs to build platforms by the Navy’s deadlines.

According to Brian Fields, HII’s vice president of USS Enterprise (CVN-80) and USS Doris Miller (CVN-81) aircraft carrier programs for Newport News Shipbuilding, this unfolding innovation is just the beginning.

“I want CVN-80 to also be the first 3D-printed ship,” Fields told reporters Wednesday during a media briefing at the Surface Navy Association’s annual symposium. HII was tapped to build CVN-80, which is slated for delivery to the Navy in 2028.

“So, we are pushing hard. I’ve got a long list of parts that I’m struggling to get because of manufacturing processes,” he said.

Getting comfortable with new processes

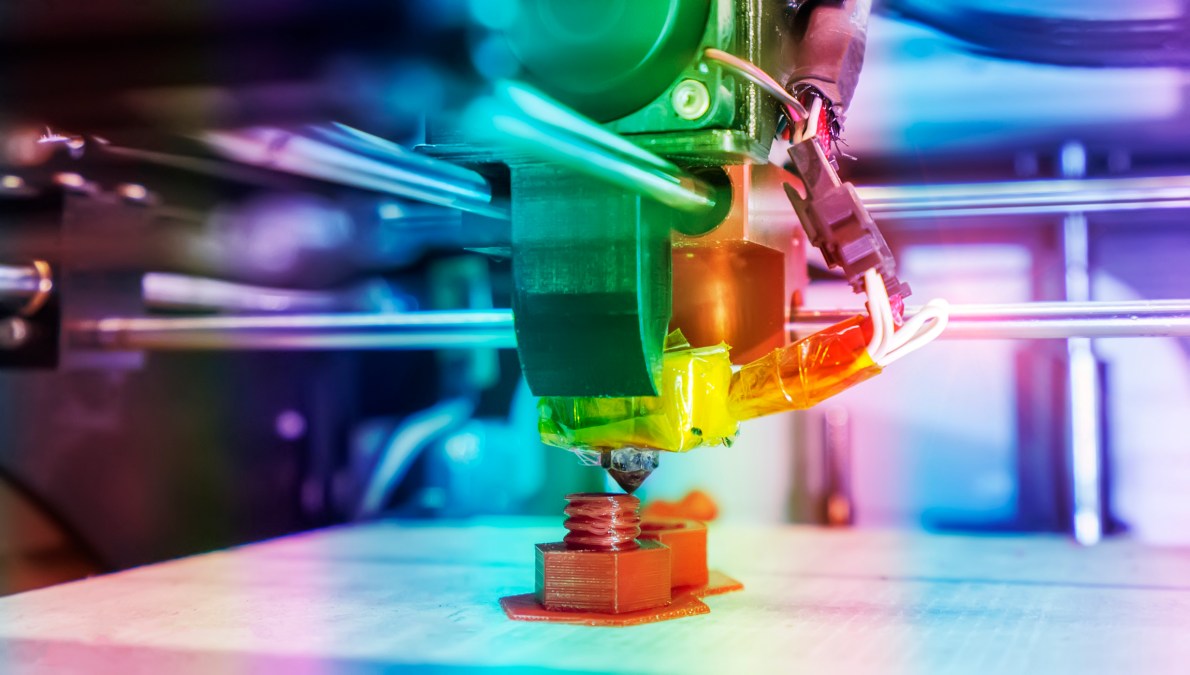

Through additive manufacturing, officials construct three-dimensional objects using data computer-aided-design software or special object scanners.

There’s been a lot of talk about the promise 3D printing holds for the government and military over the last decade, but Fields said a few factors are accelerating its use for such applications in recent years.

“Number one, I think the technology is getting better,” he explained.

Tools that underpin 3D printing have been around for a while. But Fields said 10 years ago, there were no qualifications, procedures or specifications approved by the U.S. military to apply such processes to engineer components of its assets.

“So, really, for the last three or four years, we’ve invested heavily and gotten [Naval Sea Systems Command or NAVSEA] to approve this — ‘you can print this material, on this machine, using these process controls’ — and now we can start going forward with that,” he said.

New manufacturing processes generally require comprehensive non-destructive testing before getting the OK for military applications. Fields said he thinks “all of that I think is starting to get behind us, so now the production can start to take place.”

He and other officials provided several examples of how HII is already 3D printing ship parts to stay on top of the Navy’s demanding schedule for new and sophisticated systems.

“I was supposed to erect a large superlift on CVN-80 this last March. In November, we found that the cast part wasn’t going to be available until like June or July,” Fields recalled.

His team “absolutely had to have” the systems installed on time — but they were severely limited by one single, unavailable part.

“And so with the Navy team, we designed, qualified, 3D printed, machined, and had that part in four months. I mean, I’ve never in my career seen the Navy get through a procedure qualification [like that],” Fields said.

“I’m not going to tell you what part — but I’ll tell you that you’d be shocked if you knew where this part was. It was a very critical part to the ship,” he added.

JP-5 manifolds are components that move jet fuel around the Navy’s ships. They’re vital, but it’s very difficult to fabricate them using traditional methods for a number of reasons.

Fields’ team recently 3D printed a replica of the component, which is now on display at an HII corporate headquarters office.

“I want it on a ship, but we’re working on that,” Fields said. He added that this “example of all the time and money spent trying to get those parts to me so I can get them installed on the ship on time is where I see 3D printing being able to really move the needle.”

Still, with the innovation and convenience additive manufacturing is ushering in for HII, there’s also some challenges in scaling it all, at least for right now. In the case of the needed part for the superlift, the company subcontracted a small supplier that was able to print it within days.

However, “it took a long time to get the technical community comfortable [to use it], and understandably so,” Fields said, noting that many shipbuilders aren’t immediately comfortable inserting entirely new processes in place of approaches that have been trusted for decades. He said his team is therefore currently focused on working with the NAVSEA technical community to achieve appropriate qualifications by material type based on their needs.

“The Navy is investing heavily in qualifications of additive manufacturing — not just from the processes and the machines, but the people. So, there’s a lot of money going into developing the operators on this. And the process controls have to have the right parts, especially on the warship,” Fields noted.

‘Dam breaking’

Despite the success additive manufacturing is having on the making of carriers so far, the Navy has historically raised concerns about the safety of 3D printing parts for its submarines.

For subs, there’s a deeper level of pedigree for safety and more technical oversight from the Navy. HII aims to build more and more trust through 3D printing “lower risk” parts for the military’s aircraft carriers — and ultimately also apply these processes to other types of vessels. In both the “submarine and carrier world,” programs have defined needs and areas where their supply chain is strapped.

“I think it starts there. So, one of the pressures for the ‘dam breaking’ is the customer at the end screaming, ‘I need this!’ I think that’s starting to accelerate some of that,” Fields said.

In his view, 3D printing is still such an emerging field that it has yet to prompt major discussions around the intellectual property of parts. The Navy owns and controls the printing processes and approvals around it, so the parts are less relevant than the materials and machines that make them — for now.

“I don’t know that we’ve really thought that there’s an IP issue [here]. But I mean, think 10 to 15 years from now — instead of having huge storerooms on an aircraft carrier, can we have four 3D-printed machines, and you have a library catalog of all these parts, you just send them in, and you print them and use them for maintenance or repairs shipboard? I think that that’s an easy step in the future to get to,” Fields said.