Sea services explore launching new school for drone operators as fleets grow

The Marine Corps doesn’t have an adequate pipeline of trained pilots to fully operate its growing drone fleet, and Department of the Navy components need their own “school” or custom education solution for their uncrewed systems-aligned workforce, Gen. David Berger told lawmakers on Tuesday.

“It’s pretty clear that relying on the Air Force [for such training] — as we have the last couple of years, we wouldn’t be where we are without them — is not going to meet our requirements going forward,” the commandant said during a Senate subcommittee hearing on the fiscal 2024 budget request for the Navy and Marine Corps.

Berger and other military leaders are exploring “a couple options” to solve those evolving instructional challenges, he confirmed, which include “opening up a Naval school for unmanned pilots, ourselves,” or leaning on contractors.

Uncrewed aerial systems and other emerging drone technologies are a major enabling element of Force Design 2030 — the Marine Corps’ big plan to reshape its combat power for future fights against high-tech adversaries.

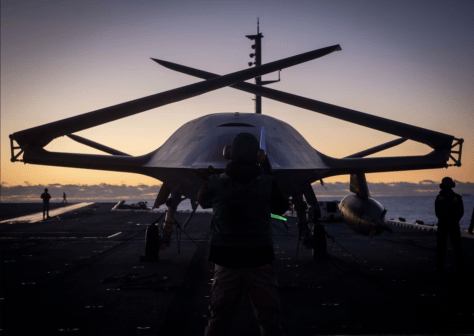

In 2020, the service set up a new military occupational specialty for operators that can advise commanders on deploying larger “Group 5” unmanned aerial systems, such as MQ-9 Reaper drones. Marines have been using those lethal, long-endurance, remotely-piloted aircraft in the Middle East since that year, with a great deal of training support from the Air Force.

In May 2022, Berger told Congress about the Marine Corps’ plans to “expand the number of [drone] squadrons that we’re flying, the number of vehicles that we’re buying and the number of people that need to be trained” — with the near-term priority being to push “them out into the Pacific” to ultimately help deter China. Then, in August, the Navy awarded a $135.8 million contract to General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, Inc. for eight MQ-9A Extended Range (ER) drones to be delivered to the Marine Corps in late 2023.

The MQ-9 has wide-range sensors, synthetic aperture radar, significant loitering and surveillance capabilities, and the capacity to strike targets via the weapons it carries.

“While our commitment to uncrewed systems is unshakeable, we have concluded the Air Force’s capacity to generate trained MQ-9 UAS officers is insufficient to satisfy Marine Corps requirements,” Berger said in his written testimony ahead of Tuesday’s budget hearing.

“At present, half of our total inventory of UAS officers (72 of 148) are not yet trained and qualified to operate the MQ-9. We are working with the Air Force to remedy this throughput issue. However, there is a need to direct the necessary resources in future budgets to establish a Naval UAS School to resolve this larger joint force issue,” he wrote.

Responding to questions on that matter from Sen. John Hoeven, R-N.D., at the subcommittee hearing Tuesday, Berger confirmed that senior Navy and Marine Corps officials are exploring the potential of launching a UAS school of their own.

“We don’t know yet what that would cost, where we would put it, the instructor base — all that sort of thing,” Berger said. However, “it’s pretty clear” to them that “relying on the Air Force” probably won’t be the best move as the sea services’ drone deployments continue to expand and mature.

Spokespersons from the Navy and the Marine Corps have yet to provide DefenseScoop more information on this training requirement.