Fixing munitions shortages demands better hardware and new software

Since the first V-1 flying “buzz bombs” streaked across the English Channel towards London during World War II, the cruise missile has evolved into a family of highly sophisticated munitions which, because of their ability to accurately hit targets at 1,000 kilometers or beyond, have become a mainstay of U.S. military advantage, diplomatic force, and deterrence.

The most recent strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities relied on more than 30 Tomahawk missiles fired from an attack submarine. Early last year, more than 80 Tomahawks struck targets in Yemen to kick off a month-long American and British campaign against Iran’s Houthi proxies. However, more Navy cruise missiles were expended in these two brief operations, against militarily unsophisticated adversaries, than the Pentagon requested and Congress funded over the same period.

America’s anemic production rates of these and other crucial munitions loom large in deterring aggression in the Indo-Pacific. Here, the vulnerability of U.S. bases and aircraft carriers would require the U.S. military to have the ability to hit an enormous number of Chinese targets well beyond the range of most of its land- or carrier-based combat aircraft. A series of think tank wargames concluded that a conflict in the Taiwan Strait would consume multiple thousands of long-range strike munitions that would exhaust available U.S. inventories within three weeks.

“God forbid, if we were in a short-term conflict, it would be short-term because we don’t have enough munitions to sustain a long-term fight,” Rep. Tom Cole (R-OK), chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, warned during a recent hearing.

The potential gap between our military needs and industrial throughput is jarring. It calls not only for expanding the numbers and variety of munitions suppliers, but also for deploying the most innovative software in the Defense Department to proactively and assertively oversee them for outcomes.

America’s traditional defense industry — working through the traditional defense acquisitions system — continues to make the world’s advanced weapons with often spectacular results, as we saw with the B-2s and bunker busters in Iran. But the process is akin to the artisanal production in medieval guilds. Each advanced munition — from long-range strike missiles to missile-defense interceptors — costs millions of dollars to produce and several years to build.

In recent months, the Defense Department has provided seed funding under the Defense Production Act for more suppliers of solid rocket motors and energetics, stood up a “Munitions War Room,” and engaged the prime contractors directly and pointedly to boost production rates.

Congress has done its part by, after years of DOD requests, authorizing the use of multi-year procurement for long-range anti-ship and air-to-ground missiles (LRASM, JAASM) and missile interceptors (PAC-3 “Patriot”).

The Pentagon should take advantage of non-traditional technology companies — hardware and software makers alike — to furnish a constant flow of actionable options, alternatives, and expanded output. That also involves the DOD articulating a “good enough” set of specs for cruise and interceptor missiles that meet minimum requirements for range, payload, speed, precision, electronic warfare shielding, and compatibility with existing U.S. air and naval launch platforms.

“We need to look at other vendors,” Acting Chief of Naval Operations Adm. James Kilby told the House Appropriations Committee. “They may not be able to produce the same exact specifications, but they might be able to produce a missile that’s effective, which is more effective than no missile.”

New industry entrants are stepping forward with alternative offerings. Others are taking advantage of 3D printing and modular design to produce cheaper missiles that can still get the job done. The question is whether they will get orders from DOD and, equally important, whether they can deliver at scale and on time. The same goes for traditional contractors who are willing to introduce lower-cost alternatives to their profitable incumbent munitions programs.

The usual market solution — increasing orders (and thus demand) for needed munitions — is necessary but insufficient. The underlying structural challenge is capacity and supply — an American industrial base that is not big enough to generate enough materials, metals, chemicals, batteries, sensors, and micro-electronics to surge long-range munitions while also supplying other military weapons systems and commercial products.

For example, after a series of corporate consolidations there are now only two qualified providers — down from six in the 1990s — of military solid rocket motors, a leading cause of munitions production delays. Other rocket motor vendors — Anduril, X-Bow, and Ursa Major, for instance — are coming online with DOD support, while still years away from commencing new production.

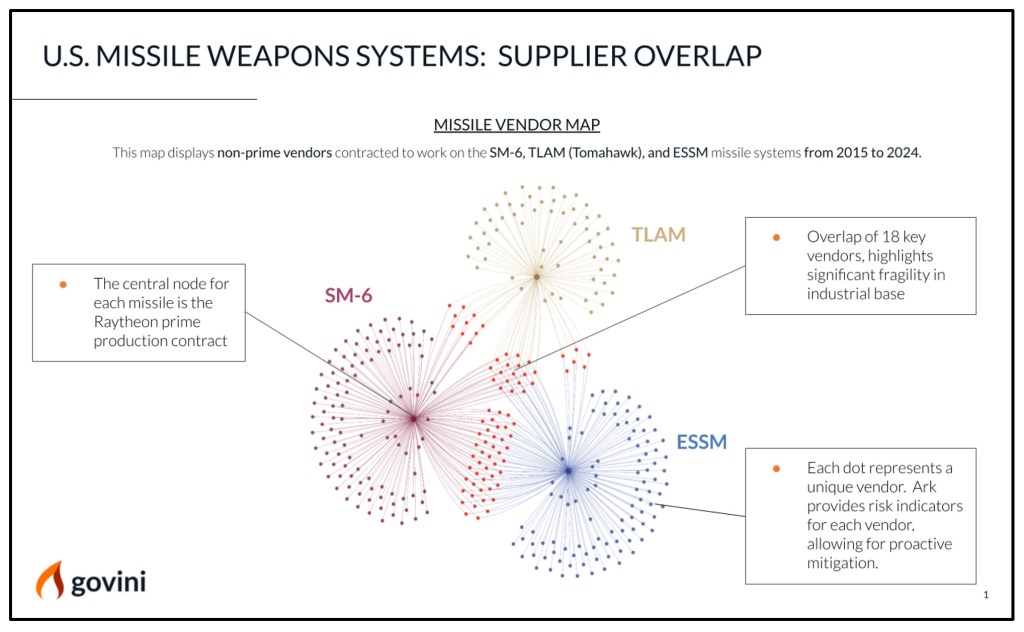

The problem is systemic across multiple advanced munitions systems that share and compete for the same scarce components.

Yet, defense supply chains are still mostly tracked and managed as individual programs, often in manual spreadsheets, without the relevant puts and takes on the broader industrial base. For crucial components information, DOD depends way too heavily on the willingness of prime contractors to divulge their own data. Defense leaders lack the modern data capability to hold the primes accountable, and the primes’ own ability to harness the industrial base is more mid-20th century than early 21st. What defense planners need is the AI capability to track and prioritize scarce items across the broader munitions supply chain enterprise, and enable action. The good news is: that AI exists today, out-of-the-box.

Modern data science and analytics make the difference by providing a comprehensive view of supply chains from final assembly at the prime level, down multiple tiers of sub-components, and further down to the smallest washers and widgets. AI-enabled software integrates both internal program data and publicly available information (on competing demand, alternative parts, shipping routes, company financial health, foreign ownership, etc.) to identify vulnerabilities and gaps while generating alternative solutions. For example, identifying a commercial part with 95% commonality to the item holding up military production.

Reversing the post-Cold War consolidation and withering of America’s defense industrial base — for munitions and everything else — might be the work of years, decades even. But, harnessing the industrial base we have exponentially better than we currently do is within our power now, with defense acquisition software to increase yield.

By opening the door to new partners, better utilizing our existing industrial bases, and enabling speed and affordability, America can regain its strategic edge and ensure its forces are never left wanting for the munitions they need to win.

Jeffrey Jeb Nadaner is a senior vice president at Govini, the defense acquisition software company. He served as the deputy assistant secretary of defense for industrial policy in the first Trump administration.