Space industrial base racing to meet growing demand for military satellites

SIMI VALLEY, Calif. — Over the next decade, the Defense Department intends to proliferate hundreds of new military satellites on orbit that will provide improved space-based capabilities for warfighters. While the effort has been lauded as an ambitious and innovative plan to revolutionize space acquisition and development for the modern era, it has also exposed critical vulnerabilities in the United States’ ability to manufacture and deliver systems at scale — an issue that both the Pentagon and industrial base are working to learn from moving forward.

“We do not have the industrial capacity built today to get after this,” Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. Michael Guetlein said Dec. 7 during a panel at the Reagan National Defense Forum. “We’re going to have to start getting comfortable with the lack of efficiency in the industrial base to start getting excess capacity so that we have something to go to in times of crisis and conflict.”

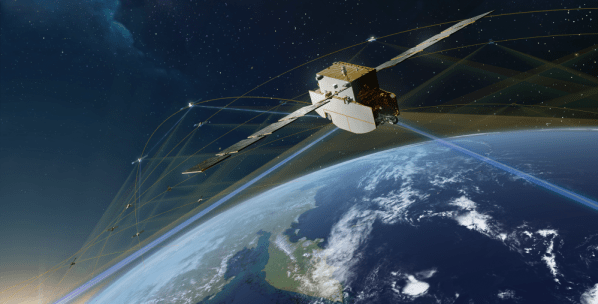

Resilience through proliferation

Historically, the Defense Department tended to develop a few very large and exquisite satellites to conduct critical military missions. But with the growing use of space as a warfighting domain by both the United States and its adversaries, the Pentagon is now focusing on different ways to build resilience in its space systems — such as by launching hundreds of smaller, inexpensive satellites for a single constellation.

At the forefront of the relatively novel approach is the Space Development Agency’s spiral acquisition strategy that is being used for the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA). Once it’s built out, the constellation is expected to comprise hundreds of satellites in low-Earth orbit (LEO) and include space vehicles carrying different communications, data relay, missile warning and missile tracking capabilities.

SDA plans to field systems in batches every two years, with each iteration carrying the latest technology available. Although the first operational satellites known as Tranche 1 were slated to launch in fall 2024, that deadline has since been delayed to March or April 2025 due to supply chain bottlenecks, according to SDA Director Derek Tournear.

“I will say that what we’re seeing in the supply chain in the small LEO market has caught up to what SDA’s needs are, but it took them about eight months longer than they anticipated to ramp up,” Tournear said during a panel at the Reagan National Defense Forum.

A total of 158 satellites are being developed for Tranche 1 of the PWSA: 126 data transport sats, 28 missile warning/missile tracking sats and four missile defense demonstration sats. The agency will also launch 12 tactical demonstration satellites under the Tranche 1 Demonstration and Experimentation System (T1DES) initiative to test new capabilities that can be leveraged in future PWSA tranches.

Across that order, four prime contractors are on the program — York Space Systems, Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin and L3Harris — and each of them is working with dozens of subcontractors.

Executives from various Tranche 1 primes who spoke to DefenseScoop acknowledged that they encountered supply chain bottlenecks in their work for the contract. Issues have now mostly been resolved and the vendors are on track to launch by the new deadline, they said.

However, companies are still using those lessons learned to mitigate setbacks for future tranches that go beyond just purchasing long-lead items.

“We’re seeing the results of that demand signal that SDA has been sending us on a very consistent basis through their spiral tranche acquisition. Is it perfect yet? No. We’ve got some places to go,” Rob Mitrevski, vice president and general manager of spectral solutions at L3Harris, said in an interview.

Tranche 1 isn’t the first time SDA has experienced delays. The agency was forced to push back the launch of Tranche 0 — a group of 27 satellites that served as a proof of concept for the entire PWSA — by about six months.

The holdup was attributed to supply chain bottlenecks that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic when many manufacturers were forced to slow or stop production lines. Specific microelectronic components such as resistors were particularly difficult to buy, Mitrevski noted.

The recent issues aren’t caused by COVID-19 conditions, but are instead reflective of the sheer volume of systems SDA is asking of its contractors and an industrial base that wasn’t quite ready to meet the increased demand.

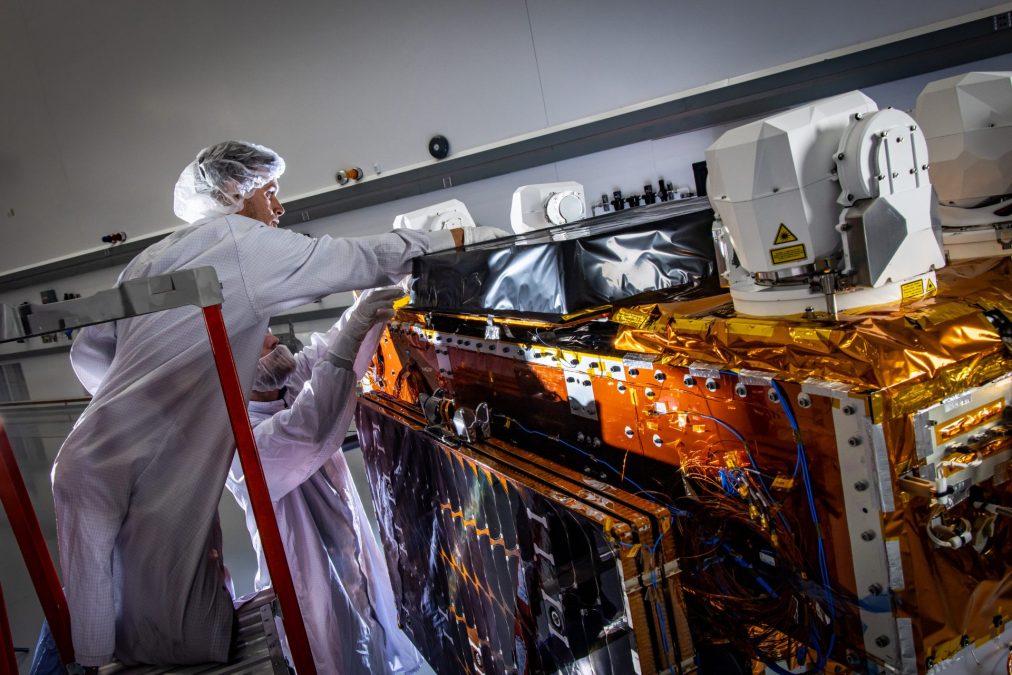

“I think a lot of that has been just scaling — getting past designing tens of things to designing lots of things,” Louis Christen, senior director of proliferated systems at Northrop Grumman, said during a tour of the company’s Space Park facility in Redondo Beach, California, where it’s manufacturing Tranche 1 birds.

To alleviate potential risk, Northrop Grumman has been moving through production as much as possible and building multiple satellites in parallel, Christen said. Working very closely with its multiple subcontractors throughout the process has been another critical strategy.

“Although they’re commercial suppliers, we’re not just buying stuff from them. We’re a partner. We’re there on a daily basis and helping prop them up,” he said.

Dirk Wallinger, CEO and president of York Space Systems, said challenges the company had weren’t specific to its Tranche 1 contracts, but actually reflect a lack of diversity in the supply chain that is affecting the entire space industry.

“One of the key bottlenecks results from [requests for proposals] with subsystem performance specifications that inadvertently narrow the qualified vendor pool to a single supplier,” Wallinger told DefenseScoop. “This limits the value tradeoffs of all of the prime contractors and by creating dependency on sole-source suppliers, exacerbates delays.”

Addressing the problem would require rethinking high-level performance requirements in a manner that would diversify the supplier base and enable more competition in industry, he added.

L3Harris is also trying to move away from single or sole-source suppliers by building strong relationships with the swath of subcontractors it has worked with on all three of its contracts for the PWSA, Mitrevski said.

“The supply chain works to create scale over time, and the scale is created through a diverse group of suppliers,” he said. “What you’ve seen in the way we’ve evolved from [Tranche 0] through now [Tranche 1] and [Tranche 2] is a continual improvement of the scale and diversity in that supply chain.”

Wallinger noted that they’ve found the most effective way to mitigate supply chain risks has been to buy satellite buses from providers ahead of receiving mission specifications. In the future, it’s crucial that the government secures these long-lead items as early as possible to effectively eliminate delays, he added.

“Schedule risk is mostly induced from bus component suppliers, not mission payload developers,” Wallinger said. “Commoditized satellite buses are the only ones being considered, and by definition can support a range of mission sets. They are the critical component to procure in advance.”

Mitigating future delays

While SDA has tried to ensure its system requirements can leverage readily available hardware, Tournear said there are some components that must be tailor-made for the Tranche 1 satellites. Mesh network encryption devices that are approved by the National Security Agency have been a significant headache because there’s only one manufacturer able to make them, he said.

The agency has adjusted its timeline expectations for future PWSA tranches to allow more time for vendors to build their platforms, adding several months to overall production time.

Mitrevski also noted that SDA’s overall strategy to fund development of capabilities that can be tested early on is beneficial.

“They have a number of efforts where they’ve clearly acquired leading-edge capabilities with the intention of driving the maturity level of those leading-edge capabilities forward and then make use of them later on,” he said.

York Space Systems has also discussed with SDA ways to mitigate risks outside of supply chain diversification, Wallinger said. One area of improvement could be ensuring long-lead items are aligned with current and future mission requirements, he noted.

“We have had several instances where the second- and third-tier suppliers had stock on hand, but that stock didn’t have the right interface protocols or didn’t have the right form factor, and couldn’t be used to meet the actual mission needs,” he said. “So you had those suppliers spending capital on things that simply had to be completely redone at a cost to the [U.S. government] and us.”

But with plans to only grow the number of military satellites on orbit — not just for the PWSA, but also other programs across the Defense Department — SDA’s work is likely going to create a ripple effect of both growth and demand within the industrial base. The supply chain woes are serving as a “canary in the coal mine” for the national security space community writ large, and will require the entire department’s effort to fix them, Guetlein said.

“Because of the quantities that he’s ordering, he’s now starting to uncover the challenges that we have with the industrial base,” Guetlein said, referring to Tournear. “And these challenges are significant, and we need to figure out how to get after them.”