- Sponsored

- Insights

Too much data, too few analysts: How AI offers a ‘force multiplier’ for intelligence analysts

For U.S. intelligence analysts, collecting data isn’t their primary challenge — it’s surviving the daily flood of it. Geospatial imagery, open-source intelligence, signals intercepts, and unstructured chatter pour in at a scale that no human workforce can possibly process unaided.

“There is too much data out there and not enough analysts available to sift through it,” said John Urby, a former Army intelligence analyst and now senior director of business development at General Dynamics Information Technology (GDIT). “Without artificial intelligence (AI) and automation, it would be impossible for analysts to get through every piece of data to verify what is valid or invalid and what’s worth continuing to look at.”

That reality is putting growing pressure on intelligence agencies and analysts’ abilities to keep up with the intelligence demands and the speed with which the White House and senior government officials increasingly need them.

From brute force to pattern recognition

Various forms of AI have been part of the Intelligence Community’s tradecraft since the start of the Cold War. What’s changing is the need for government leaders to make well-informed decisions based on intelligence analysis faster than ever before. At the same time, the surge of raw data — and the growing challenge of verifying what’s true and accurate — is shifting AI’s role from simply assisting with data collection to becoming more of a “partner” in the decision-making process for analysts.

AI is already having a significant impact on the work of intelligence analysts by helping to structure, organize, and label data — dramatically reducing the time required to sift through it from months to hours or even minutes.

In the conflict in Ukraine, for example, AI has been used to tag images with location and time stamps and identify what’s in the image, such as tanks, drones, or airplanes. This enables analysts to query and search for what matters most to them. Beginning in the early months of the Ukraine war, AI-enabled tools also helped the U.S. government quickly declassify and distribute reports that would otherwise have languished in traditional analytic pipelines.

Urby and others see AI continuing to evolve in its role. All-source analysts will shift from data gathering to more data validation and fusion, while human intelligence analysts will increasingly focus on automation for report consolidation and human interaction. AI will handle tedious, time-consuming tasks, freeing human analysts for more complex cognitive work. As Urby put it, “I don’t think it’ll ever completely outsource an analyst; I think the business is too human-centric.”

The trust factor

The rapid influx of open-source data presents a secondary challenge: validation. With the ease of AI-generated or manipulated images, distinguishing between real and fake information is becoming more critical and more time-consuming.

There are now vast amounts of commercial satellite imagery and open-source data available to analysts — but adversaries are also producing and pushing out their own imagery and false narratives. While AI tools are emerging to help identify deception, experts note it’s a constant arms race between those creating false data and those building algorithms to detect it. Urby described it as an ongoing “push and pull” between detection and deception.

With the increasing dependence on AI comes a deeper concern: trust and confidence. Intelligence professionals, long accustomed to validating the pedigree of human sources, must now also interrogate the pedigree of their algorithms.

Despite AI’s growing capabilities, analysts continue to grapple with the “black box” problem — how did the AI arrive at its conclusion, particularly when used in the decision-making loop. AI confidence ratings, while helpful, remain subjective, making it challenging to achieve unbiased and objective assessments from AI systems, not unlike what human analysts often encounter when challenged on their subjective conclusions.

To build this crucial trust, analysts are being encouraged to ask critical questions about the creation and provenance of the AI products they use. That includes:

- Where did the investment come from, and who are the people behind an AI model? If it has traces from an adversary, it’s probably not something an agency should rely on.

- Who trained the model, and what data was used for training? Was it developed using synthetic data that’s semi-realistic, or on real-world data?

- How transparent is the underlying logic? If you fed historical data into a model — such as the Cuban Missile Crisis or the 9/11 attacks — could you validate its output against what actually happened?

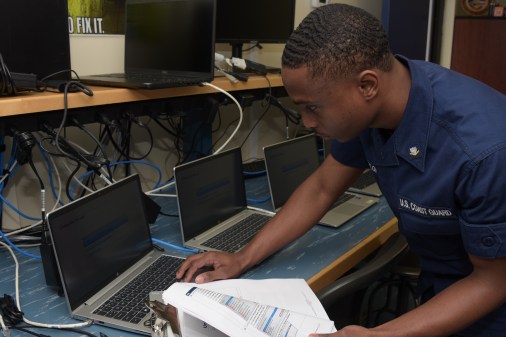

Training as a strategic imperative

These evolving dynamics of AI-assisted workloads underscore the urgent need for intelligence analysts to expand their AI literacy and skills. “Training is paramount if AI is to be trusted and used effectively,” Urby said.

Across the intelligence community, there is growing recognition that analysts must understand how AI models work, ask more effective questions of their tools, and learn how to train and interact with AI responsibly within their daily workflows. Some analysts with years of field or technical experience but no formal development background have already begun creating AI bots to automate parts of their analytical process — reducing workloads that once took a week to complete to just a few hours.

“The intelligence community’s challenge isn’t just deploying AI — it’s democratizing it responsibly,” explained Fazal Mohammed, a senior solutions architect at Amazon Web Services. “The key is providing secure, governed infrastructure that lets analysts experiment and innovate while maintaining rigorous security standards. When analysts can rapidly prototype, test against historical scenarios, and understand their models’ decision-making processes, they move from being passive consumers of AI to active architects of it. That’s when AI truly becomes a force multiplier.”

As AI tools become more accessible and integrated into daily missions, expanding technical literacy and governance will be essential. Intelligence analysts who understand both the capabilities and limits of AI will be best equipped to guide its responsible use.

This article was produced by Scoop News Group and sponsored by GDIT.

Learn more about how GDIT can help your organization leverage AI for faster analysis and decision-making.